Beneath the 1080p resolution of its millions of literal pixels glazed into the surface of this wizardly contraption, a short story by John Cheever appears. It’s in a new zine found in Apple’s newsstand app that has of late become a guilty pleasure of mine, elegantly entitled, Paragraph. It’s like the Huffington Post of literary short stories coupled with some artistic YouTube vignettes, compiling its issues with old and new stories alike.

The familiar and safe, Times New Roman font, emanates from under a screen that feels and looks like it’s out of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner—65mm. One of those great films that the children of the generation following the one that got to experience it in the movies, can look at, and feel, that it is still about the future while simultaneously being entwined in both the present and the high romanticism of a ghastly past that the 80s embalm. Such is also Cheever’s, “Of Love: A Testimony” with its narrative confidence, more than a half-century’s distance, and ass-naked bare, Terminator style, delivery of relationships, life struggles, and of course, love, which anyone who had to write about so candidly, certainly would need to be hitting the bottle like Cheever. Written in the 1940s. The nineteen forties.

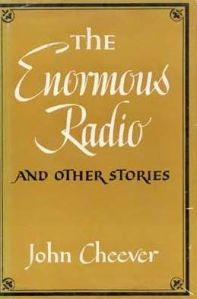

Cut to a tiny independent bookstore off Bedford Avenue. The shelves, housed in a large walk-in-closet, are stacked with yellowing covers–their fragile oxidized pages crumbling with every negligent touch. Lifting the (unknown to me) famous collection, The Enormous Radio And Other Stories, I bring it up to the guy housing the shop to buy it, and he is reluctant to part with it. After a heavy silence, he finally says, “I keep . . . . watching them go” with echos of hopeless despair in his voice. As I part, of course, the sky spells out a dark gray New York doom while bits of prickling rain hit the asphalt.

Two weeks and five books later. I open the Harper & Row edition, printed in 1965. I hold what must have been the sad proprietor’s prized possession, and as such, am ready to receive the lifeblood that I imagine has sustained him through many gloomy New York afternoons. Then I envision a stretch of yellow flowing spandex on which pot-smoking hippies jump upon as if it were a trampoline, their long hair swiveling through the air as I envision the previous owner walking about with the book in the sixties sun. The first letter of every story in this edition is in large curly calligraphy that was typically used in nineteenth century newspaper headlines. Each story is full of nostalgia and in some way or another is dealing with the ever-present past. All of these stories were published in the New Yorker from the late 1930s to the early 1940s and were written in the span of three and a half years.

Two weeks and five books later. I open the Harper & Row edition, printed in 1965. I hold what must have been the sad proprietor’s prized possession, and as such, am ready to receive the lifeblood that I imagine has sustained him through many gloomy New York afternoons. Then I envision a stretch of yellow flowing spandex on which pot-smoking hippies jump upon as if it were a trampoline, their long hair swiveling through the air as I envision the previous owner walking about with the book in the sixties sun. The first letter of every story in this edition is in large curly calligraphy that was typically used in nineteenth century newspaper headlines. Each story is full of nostalgia and in some way or another is dealing with the ever-present past. All of these stories were published in the New Yorker from the late 1930s to the early 1940s and were written in the span of three and a half years.

As is usual in such cases the reader gets to observe a writer’s literary development and emotional trajectory through time. But the impressive zing of my first encounter is largely gone; the frail pages, stripped of their lustre, stifle with their tightly packed realism filled with formal addresses: Mr. Fellows; The Whittemores; The Hartleys; Mrs. Brownless; the early narrative structures are ordinary and predictable; the titles, unbearably poetic: The Pot of Gold; Goodbye, My Brothers; O City of Broken Dreams; Torch Song; all of which I love, were it not for the disharmony that they exhibit with the stories that they hat. How does one not envision distraught New Yorkers, scattered around the J train under the shudders of dim yellow lights, seen from a distance, crawling along the side of the bridge like some topaz necklace into the cavernous swallows of brilliant city streets filled with jazz clubs and slums after reading, “O City of Broken Dreams?” How not to run to the bottle and throw on some Benny Goodman or Coltrane? Where is that music in the narrative? Ah, but there are reserves. Under my sphenoid is Mad Man, and its latent language, as exhibited by the middle and upper classes, is overbrim with the cadences of the forties, which help me hear Cheever and allows me to animate his ‘stillborn babies.’ To feel the heat of their souls.

Would I react differently if I read these early stories under the gloss of a shiny screen? This is a serious question, not to be brushed off with, a word is a word kind of logic. A chair is a chair but to sit in a vintage chair is quite a different experience than to sit in an ultramodern chair; the style’s name alone has a kind of nauseating psychological force built into it. So I fight past the stale pages of which critics have written theses on, overlooking the Calvinist verses Protestant philosophies buried beneath the dialogue, as James O’Hara offers–that bread and butter of English professors–into “The Pleasures of Solitude.” I do however stop to note and admire Cheever’s choice of placing his punctuation within his quotation marks. Pedantry be damned. This is the first story in the collection, beside the originally spurring one exhibited in Paragraph, which knocks me upside my rusty chin.

Cheever not only packs a punch into five and a half pages, but augments his narrative (stating the plot will spoil it) with these gorgeous, on the surface superfluous touches that display some of the best gestures of realistic writing, “She thought of calling the police, but when she tried to describe what had happened as if she were talking to the police, it sounded unconvincing and even suspicious.” It’s that, “and even suspicious” part that really strikes. That soft, precise detail, which more than simply conveying an aspect of character, draws the reader into the prose by subtly acknowledging a revealing communal phenomenon. It is through this, more than the drama or the sympathetic characters and even the dazzle of his metaphors that win my heart–for it is through such revelations that bits and pieces of what it is like to live in a city, New York of all cities, that end up glimmering through the lusterless pages.

The smooth manner in which he uses proper nouns, dropping them like VB-6 Felixes, sparingly, so as to ignite an entire sentence, at the right time, is reminiscent of Hemingway’s spare and poignant use of adverbs. If only MFA graduates would escape their commander’s tiresome drilling of the importance of proper nouns, then maybe they could learn some elements of style from the masters–and use it to show something original. Here is a lovely illustration from “The Pot of Gold,” where Cheever avoids all proper nouns save for street, town and character names (with the only exception being a reference to van Gogh’s “Sunflowers”) in five pages of prose, to drop the following sentence,

They sat together with their children through the sooty twilight, when the city to the south burns like a Bessemer furnace, and the air smells of coal, and the wet boulders shine like slag, and the Park itself seems like a strip of woods on the edge of a coal town.

Now there’s an image hard to forget. And the word itself has such beautiful internal acoustics, Bessemer Bessemer. Despite Cheever’s somewhat boring, but forgivable organization of his early stories, “It was…” “There were…” “It did..” he really comes into his own fairly early on, definitely by the time he writes, “The Cure,” in terms of variation and sentence structure. Hitting musical notes with abrupt, two word sentences, or opening his prose into paragraph-long sentences, as he does at the end of “The Summer Farmer.”

It is true of even the best of us that if an observer can catch us boarding a train at the station; if he will mark our faces, stripped by anxiety of their self-possession; if he will appraise our luggage, our clothing, and look out of the window to see who has driven us to the station; if he will listen to the harsh or tender things we say if we are with our families, or notice the way we put our suitcase onto the rack, check the position of our wallet, our key ring, and wipe the sweat off the back of our necks; if he can judge sensibly the self-importance, diffidence, or sadness with which we settle ourselves, he will be given a broader view of our lives than most of us would intend.

That is the broad view that I see in the positions Cheever’s sentences take.

Much of the beauty in his writing is in how intently aware it is of what it means to live in a heavily populated metropolis. Which brings me to the title story, “The Enormous Radio.” Parting with his technical form, let’s observe his leitmotif, culminating in that fantastic tale, which always is sort of in the background of his stories anyway, as atmosphere is, which we come to know through an unspoken, mutual understanding between the writer and the reader. You know, like the fact that we’re reading about other people’s lives. Eavesdropping on people’s conversations. Watching people in their sleep. This kind of voyeurism in art predates the analysis that Zizek offers in The Perverts Guide to Cinema, by about sixty years.

In “The Cure,” for instance, Cheever uses the first person narrator to intensify the perverse aspects of watching others, but by the time he writes, “The Enormous Radio,” he is using a stunning metaphor to unfurl the importance, the need, of observing how others live, and the dread in not doing so, through interestingly enough, an element found in magical realism. Make no mistake that it is an apology for writing and reading about others on Cheever’s part. It is, in fact, a powerful defense of literature; perhaps one of the most powerful that exist. So here’s the short end of the story.

The Westcotts are a rather bland couple–the kind that pass us by on the street and we think, ‘Oh they’re nice,’ but hope to never become–both of whom share an affinity for music. One day their radio breaks down, so they get a new one. The new radio does something strange though, for it starts to channel noises from the building in which the Westcotts live, emanating the sounds of the city (heightening that element of living in a city) and pretty soon, it starts transmitting conversations of other households. The Westcotts get the radio fixed, but Irene ends up regretting that they did, as she yearns to hear what is going on around her. All she has left are reports on the weather and the news. Music, sure. But it is suggested that music is not enough. How pale in comparison when the stage of the world has been silenced. Cheever seems to mean that we all have a need to hear, to see how others live; and that is not only okay, but vital to us.

Thus do Cheever and I part ways. It is another gray, cold morning in New York. The buildings around me feel hollow, full of his characters. Some are getting through the day by the thought of getting that Martini in the afternoon. Others are listening to Schubert on the radio with catatonic eyes. Others are checking their online banking statements. Some are planning vacations. Almost nobody smiles.